In Organizing for the Future, McKinsey organizational design consultants Aaron de Smet, Susan Lund and William Schaninger highlight the accelerating digitalization of the workplace, driven by the economics of automation. They discuss the need to “rethink organizational structures, influence, and control” in this context.

Their narrative is very much geared to the global multinational private sector corporate audience – the client and stakeholder constituency that global strategy consulting organizations like McKinsey, BCG and others serve. They frame the challenges these organizations face in embracing agility and innovation: to be both stable and dynamic, making the most of their big-company advantages, while keeping pace with disruptive innovators.

One might think of increasing automation as a continuation of the work started by early industrialists, such as Henry Ford, embracing the systematic mass production of inexpensive goods coupled with the payment of high wages to workers. In today’s economy, others see this process as fundamentally different, with automation now focussed on growing production levels, while increasing the pool of surplus, underemployed or unemployed labor. It is not hard to predict where individuals divide along capitalist versus socialist lines; and it seems the divide is getting wider, and the rhetoric more polarized.

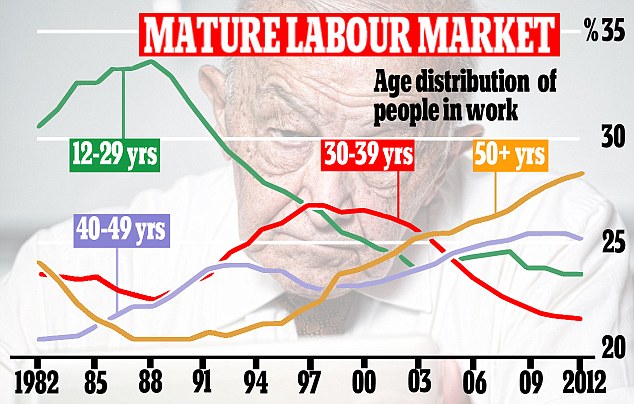

The other big secular driver of change is the aging of the workforce – a global phenomenon from Japan and China through Europe to the Americas. Even in the US, the world’s largest and most dynamic economy, fundamental changes are under way in the structure of the labor force, driven largely by declining participation rates as older workers leave the workforce and a larger percentage of younger workers of all ages head to school for retraining and retooling to fit into the “new economy”…..or elect to drop out of the workforce entirely. Australia’s experience is illustrative:

The other big secular driver of change is the aging of the workforce – a global phenomenon from Japan and China through Europe to the Americas. Even in the US, the world’s largest and most dynamic economy, fundamental changes are under way in the structure of the labor force, driven largely by declining participation rates as older workers leave the workforce and a larger percentage of younger workers of all ages head to school for retraining and retooling to fit into the “new economy”…..or elect to drop out of the workforce entirely. Australia’s experience is illustrative:

Large organizations everywhere are seen as being increasingly vulnerable, in an age of disruptive, technology driven automation. Clarity around workers’ roles, and the processes supporting them — the bedrock of decades of management practise — is viewed by these authors and others as a foundation that has turned from rock solid to “quicksand”, trapping organizations in traditional, slow moving and fast sinking patterns as their business environment changes around them. This sentiment may be compounded when one things of the large, old organizations as primarily staffed by an ageing workforce….big chunks of which are heading rapidly towards retirement.

Most people think Uber when they think of disruption…this large pool of ride sharing non-employees who are embraced – mostly – by young underemployed urban professionals who are in search of a lower cost transport solution and who are also untroubled by the market disruption and job displacement consequences (to older people) of the choices they make. Within a short span of years, Uber has transformed the regulatory, business and labor market structures of a long established taxi industry…an industry with the cliched “PhD” drivers that was for years the first job stepping stone business of hundreds of thousands of immigrants coming to new societies seeking a better life for themselves and their children.

What will happen when these forces — changes in automation and a fast ageing employee demographic — impact at multinational scale in industries like financial services…and in core markets…such as the retail, commercial and investment bankers of London, New York, Hongkong, Toronto…you name it. Many of the world’s largest financial centers are disproportionately dependent on their FI businesses for employment and taxes. What happens when these jobs disappear?

What does automation portend here, as we scan deposit our cheques, do our personal and business banking transactions from our mobile devices, operate our online businesses from tablets linked to non-bank owned payment engines, and seek equity and debt capital from non-traditional lenders through online portals?

The 5 largest Canadian Schedule 1 chartered banks — among the world’s most conservatively managed financial services businesses — are rumoured to see in excess of $250 billion in collective profits at risk of loss in the coming decade from disruptive innovation in financial services technologies. For financial organizations world wide that number easily moves into the trillions. That is a lot of cheese…and a lot of job losses and anxiety! Is being conservative good? or increasingly risky?

The disruptors are not simply start-ups launched by inexperienced university graduates…they are technology giants like Google and Apple looking to muscle their way into the payments systems and other financial industry backbones as a way to retain their own growth profiles. If you sit in a C-suite spot at any bank in any OECD country and think about how Google and Apple absolutely destroyed Blackberry in a matter of few years by out-innovating them, you are bound to be nervous….very nervous.

Whether looking to protect their turf in finance, telecom, media, manufacturing – anywhere – organizations must of necessity be engaged in a fundamental reimagining of their organizational structures, systems, processes and people…and, as we have seen in earlier blogs, a continuing shift away from (higher cost) people to (lower cost) automation to maintain profitability and dividend growth.

As the McKinsey team notes “most of the organizational ideas of the last half-century or more have taken for granted the underlying building blocks of jobs and the way people work, both individually and together”.

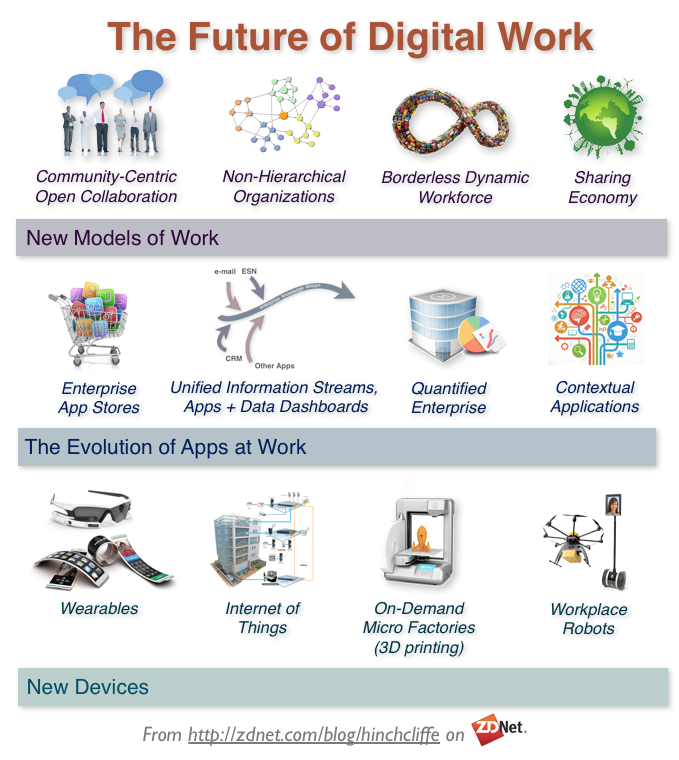

With automation encroaching on an increasingly range of skills and able to perform many tasks formerly the preserve of workers – and managers – organizations and individuals are being necessarily forced to reconceptualize the very idea of work, and what a job is….or, as many are doing, simply opt out of the entire process.

“Once roles and tasks are sorted out, the newly constructed jobs that result must be reaggregated into some greater whole, or “box,” on the org chart. Those boxes then need a new relation to each other. Will the destabilization of jobs prove powerfully liberating to organizations, making them far more agile, healthy, and high performing? Or will it initiate a collapse into internal dysfunction as people try to figure out what their jobs are, who is doing what, and where and why?”

Moving down from 30,000 foot strategy level, organizational structure and organizational design play an increasingly important, and still under appreciated, role at the day to day operational level as organizations seek to transform themselves in an unpredictable and structurally different business environment.

Moving down from 30,000 foot strategy level, organizational structure and organizational design play an increasingly important, and still under appreciated, role at the day to day operational level as organizations seek to transform themselves in an unpredictable and structurally different business environment.

As organizational performance and design consultant Ron Capelle recently noted, in How To Find the Right Number of Layers for your Company most of us are oblivious to organizational design….“It tends not to be on the agenda .”

At Organimi, our mission is to help organizations create, manage and share this organizational design information – faster and easier – so they can make this transition to more adaptive, innovative and agile organizational architectures successfully, engaging a changing workforce in the process.

In coming blogs through 2016 we will explore this topic further.

Meanwhile, if you want to explore Organimi more, and what it can help you do for your organization, please join our community.

As always, thanks for reading.

The Organimi team.